When the Rave is Done

23 → 27.10.2017

Curated by KEIV

Participants :

Antonis Kalagkatsis

Timos alexandropoulos

Constantine Lianos

George Moraitis

G. Konstantinidis (AKA Voltnoi)

Giannis Galiatsos

Themistoklis Pantazakos

A result of modern reality with traces to the ancient past. A burst, as well as a brutal form of introspection, with clear structural elements as well as intense personal stakes.

A result of modern reality with traces to the ancient past.

A burst, as well as a brutal form of introspection, with clear structural elements as well as intense personal stakes.

A situation which brings the issues and qualities of the participants to the surface while at the same time harbouring them from their usual situations. The rave culture is without question difficult to define fully, but from its beginnings (late ‘80s-early ’90s) until today it has covered under its umbrella a huge musical and socio anthropological spectrum, reflecting

a large part of the modern psyche.

In the exhibition “When the rave is done”, six works with different reference points are synthesised, creating a narrative for the past, the future and the essence of rave, without aiming to a complete or objective description of the phenomenon.

A situation which brings the issues and qualities of the participants to the surface while at the same time harbouring them from their usual situations.

The rave culture is without question difficult to define fully, but from its beginnings (late ‘80s-early ’90s) until today it has covered under its umbrella a huge musical

and socio-anthropological spectrum, reflecting a large part of the modern psyche.

In the exhibition “When the rave is done”, six works with different reference points are synthesised, creating a narrative for the past, the future and the essence of rave, without aiming to a complete or objective description of the phenomenon.

a picture from a personal archive

Future Fossil → Constantine Lianos → installation

Future Fossil → Constantine Lianos → Details

Future Fossil → Constantine Lianos → Detail

Future fossil → Constantine Lianos → Detail

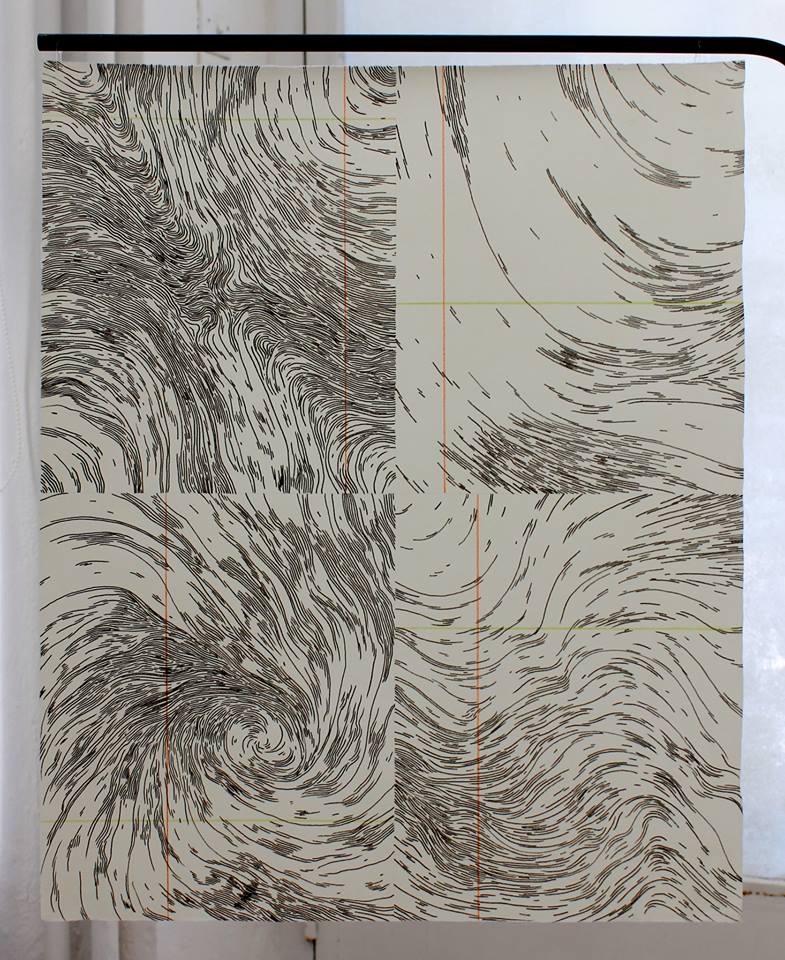

Flow Coma → George Moraitis → Digital Print (1/3)

Flow Coma → George Moraitis → Digital Print (1/3)

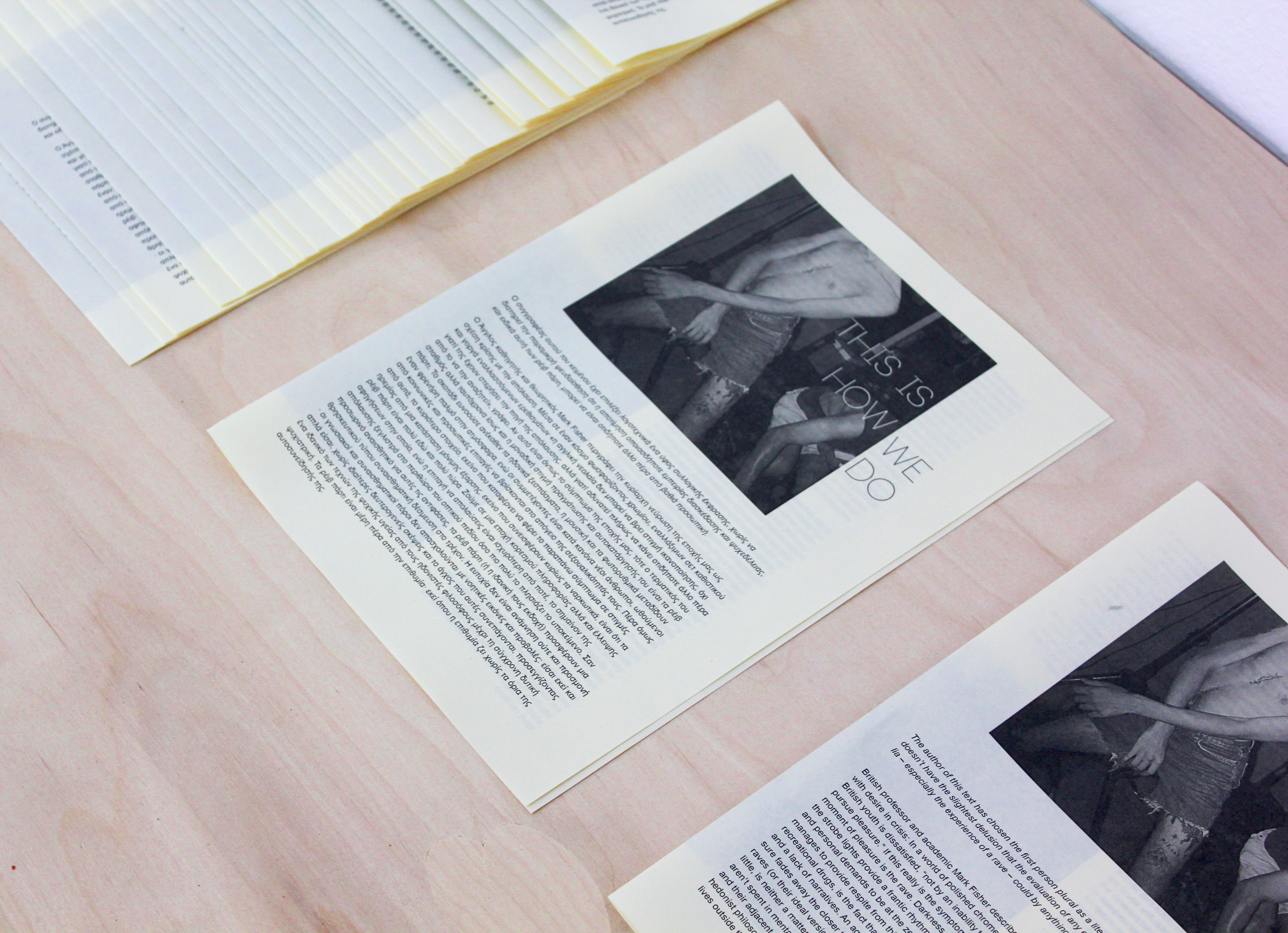

This Is How We Do

Themis Pantazakos

The author of this text has chosen the first person plural as a literary style of collective expression. He doesn’t have the slightest delusion that the evaluation of any experience related to recreation and psychedelia – especially the experience of a rave – could by anything else than subjective.

British professor and academic Mark Fisher describes the dominant neurosis of our age as a relationship with desire in crisis: In a world of polished chrome, interchangeable kitchens and rapidly alternating stimuli, British youth is dissatisfied, “not by an inability to feel pleasure but by an inability to do anything else except pursue pleasure.” If this really is the symptom of our age, then its logical end and at the same time its only moment of pleasure is the rave. Darkness was always a fertile ground for bursts of hedonism, the music and the strobe lights provide a frantic rhythm, and the participants are usually young people, pushed by social and personal demands to be at the zenith of their sexuality. Apart from the above, the main element that manages to provide respite from this symptom and its constant tension, and one helped a lot by the use of recreational drugs, is the fact that raves are here and now. We live in an age of oversaturation by information and a lack of narratives. An age in which the demand to enjoy is stronger than ever, but the signifier of pleasure fades away the closer the subject approaches. Like a temporary anesthetic to these contradictions, raves (or their ideal version) provide an almost religious emotional tethering to the present. Happiness, for a little, is neither a matter of recollection nor a matter of expectation; one’s cognitive and emotional resources aren’t spent in mental images and projections: you are there, and you simply are, without secondary thoughts and their adjacent stress. In this sense, the rave approaches an ideal of mental health, one common both in hedonist philosophers and modern western psychiatry. Raves are places beyond pleasure, where pleasure lives outside the limits of its own self-consciousness. Drug use may be an important factor in rave culture, but it certainly isn’t its only characteristic (or one exclusive to it, for that matter). Its trademark is techno music. “Why do we listen to techno?” would be a good question (apart from its historic connection with raves). For the outside observer the question would seem as self-evident as the act of listening would seem to the music’s followers, and rightly so: more or less melodic, the first impression techno gives is the persistent, constant thrust of a piston on a car chassis. Even the most ardent followers of raves sometimes admit, especially when sober, that prolonged exposure to those sounds is an act of pure madness. Aside from the obvious links of this sound to ancient pagan traditions, the key to understanding the ritual may lie within the question, “What does the music itself demand from the listener?”: In a first reading, basically nothing. The fast, hard-hitting loops of thump-thump-thump, with their minimum fluctuation, are the field of a self-consuming pleasure par excellence: they emphatically fill a space without constructing on their own any imaginary external to them. Behind them there is neither the demand to change the world or to identify with its decay (rap or punk music), nor the demand to construct a saga through images of yourself as being cool or outside the norm (rock ‘n’ roll), nor the glorification of everyday life and its protagonists (pop), not even the demand to enjoy yourself whether you want it or not, dancing on the wave of your youth and its endless possibilities (disco). With a few exceptions, like the politicized black techno in 90s Detroit, the genre’s aesthetic is its own repetition – a tendency towards a non-aesthetic. Techno is a weird music, embracing the whole of each space, played in a bizarre, intoxicated context and synthesizing the whole spectrum of its listeners’ reactions under an umbrella of inclusion. Only in raves can a person dance on their own for hours on end, dance horizontally, dance like they’re swimming on the concrete, and the next moment feel comfortable enough to rejoin the collective. Raves are among the few spaces where stimuli are so minimal, and the participants’ reactions to them so free from the influence of concrete images.

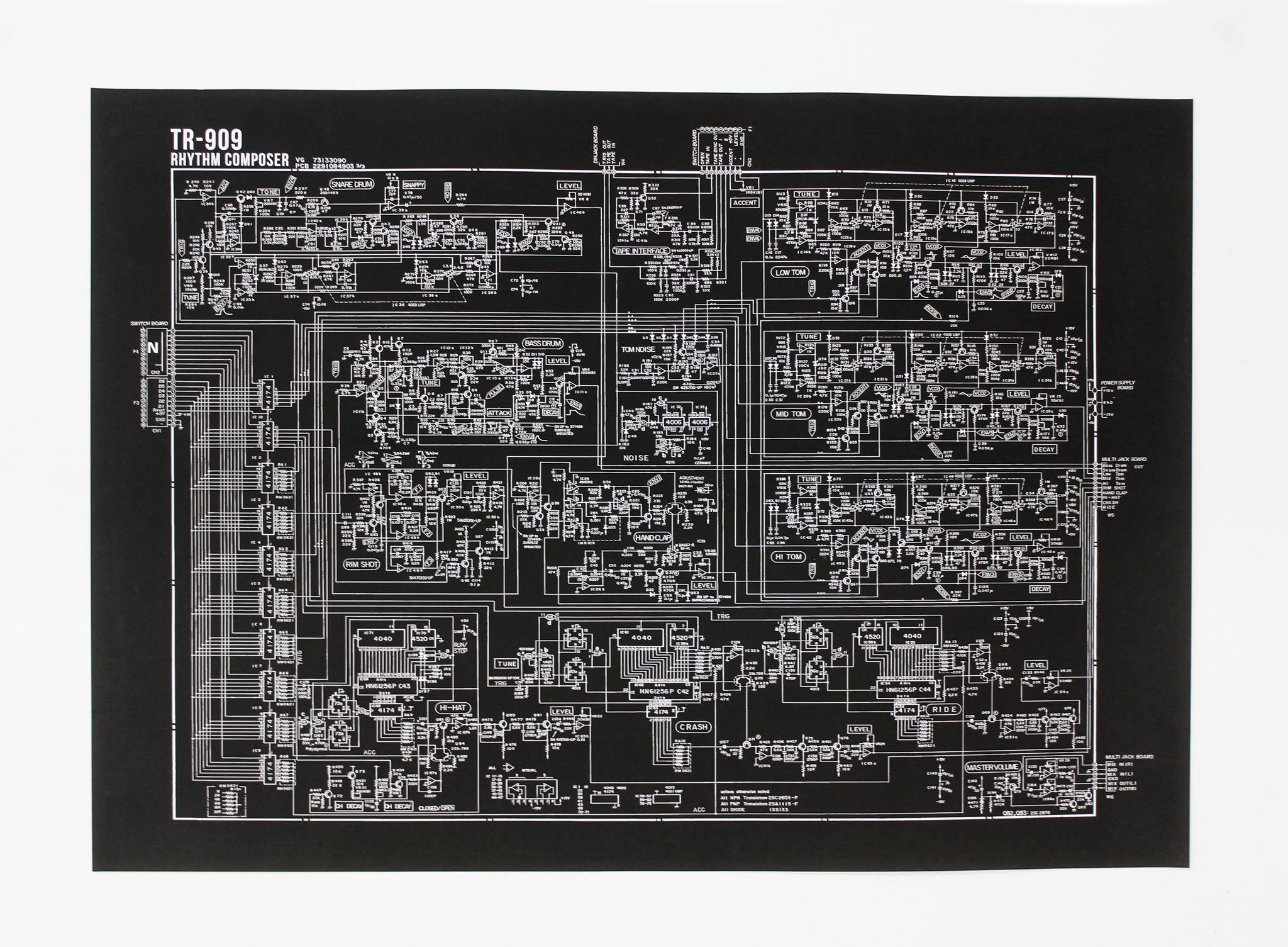

20 Techno Rave Anthems (still) → Giorgos Konstantinidis

20 Techno Rave Anthems (still) → Giorgos Konstantinidis

Audiovisual simulation (VR headset) → Timos Alexandropoulos, Antonis Kalagkatsis

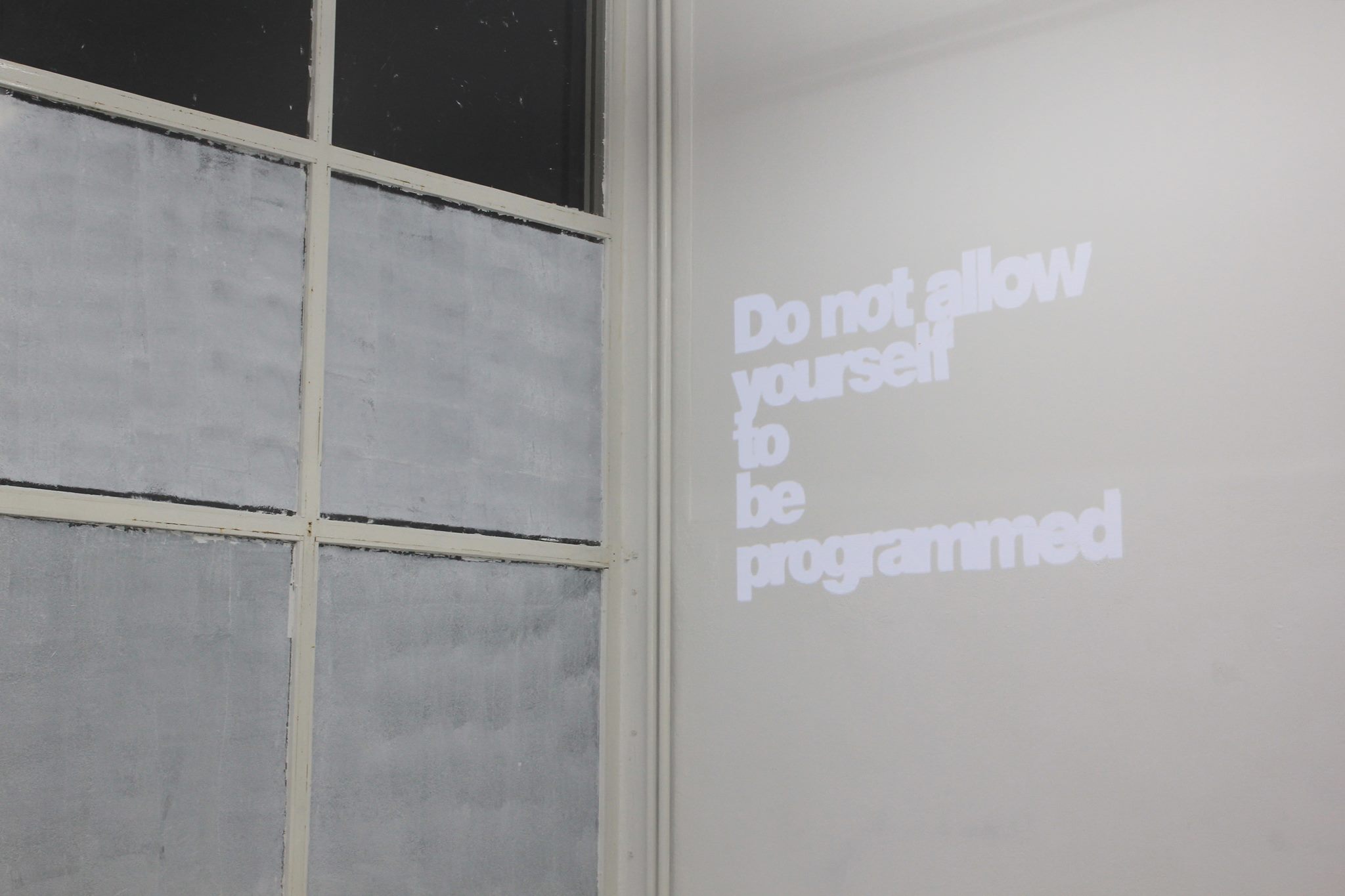

In an interesting contradiction, techno music also demands everything from the listener. It is a deterritorialized music, where the identity and the personal statements of its producers and DJs exist only in the periphery of the cultural wave in which they’re participating, and not in the music itself. The extreme end of this spectrum of depersonalization (and at the same time a statement against commercial parties where DJs are treated like idols), many DIY free party crews choose to place the DJs behind opaque pieces of fabric to distance them from the crowd and to prohibit visual contact. The sound itself doesn’t convey any explicit messages, positions or ideas; it gives the impression that it could have been made by anyone. As a result, the combination of the moves and gestures of the people dancing to those sounds end up becoming the music and the party itself, much more than in any other genre, allowing for a co-production of the experience necessary for any kind of pagan ritual. Already from the bacchanalia in praise of Dionysus and the Bacchae by Euripides we see the all-inclusive stance towards participation in ecstasy and orgasmic frenzy becoming a necessary condition for the latter. Igor Stravinski, describing the dream which gave birth to one of the most important pagan works of classical music, The Rites of Spring, talks about a circle of wise old men who stay inert while young girls in front of them dance themselves to death in order to appease the wrath of God. The healing dances of the Navajo Indians included complex purification rituals which could last up to nine days and culminated in a collective, nightlong dance, where the shamans’ role was limited to one of guidance. The Celtic origins of Halloween, two thousand years before, were based on a culture of collective production of the holiday – the decorated pumpkins and the pranks weren’t devised by any leaders. “If you see a group of people blasting trance music from a small speaker in the square,” a friend of mine once said, “you’ll understand much more about who they are and what they do in their lives than if they were playing rock music”. Techno is a kind of music which one does, possibly more than one listens to. It is tied in a very specific subculture made real in its participants’ lives.

Whatever the case may be with raves, it is certain that their organizers prepare them, wait for them and experience them with a kind of religious fervor. The process of preparation has a ritualistic aspect, both for the organizers and those who participate in the rave. Organizing such a high-decibel event in the middle of nowhere is no small task – and similarly important is the aesthetic and psychic preparation of the people who attend. A rave is an Event without any special fluctuations in terms of experience: it is a place where one goes knowing in advance that the occasion will be memorable, that it will be easy to recall images and moments afterwards: their position inside the warehouse, the changes in their emotional landscape as they alternated between different people, places and drugs. Weirdly, this doesn’t happen because raves are necessarily happy experiences for the ravers. For many of them, what follows is a period of chemical (lack of serotonin) and emotional (before/after comparison) decline, sometimes brutally so. But pleasure itself in raves has the brutal texture of serotonin over-secretion: the inability to concentrate, the tight jaws, the inhuman exhaustion, the force with which one is brought into an ecstatic place by a cocktail of stimuli, those are neither very tender nor organic: they are brutal enough to drive away the superego, stress, the demand for pleasure and the possibilities of failure. In this description full of contradictions, we should add another uniqueness of the raves: although people are generally capable of evaluating their experiences as positive or negative, raves are stubbornly disjointed experiences; even if someone has a generally good impression for the political or aesthetic aspects of the raves, they are generally incapable of deciding if a specific rave was “worth it” or if pleasure managed to overpower the resultant melancholy. Both in their evaluation after some time and as they’re experienced real-time in full, raves seem to strike an impressive balance between the mask of tragedy and comedy.

Lastly, something noteworthy in the Greek rave scene: especially in their DIY versions, raves in Athens are growing in number, while collective structures and spaces for self-organized expressions are steadily decreasing. Whether those two are related and in what way, as well as the degree in which raves are political, are questions which can’t be answered in this text. Nevertheless, we’d like to make some observations that we think would be necessary in this kind of conversation. First of all, politics (in their narrow sense) happen wherever many people are gathered in order to join a political process. We like this almost tautological definition not only because it highlights the importance of political self-consciousness and reflection (for one to be aware that what they’re doing is political and to reflect and plan on how they are doing it), but also because it does justice to the historical weight and the changes brought in the world by explicitly political movements of any kind. Apart from that, the secondary politicization of things (including raves) remains extremely important and can be mostly analyzed in the following: the kind of culture they promote and its political aspects, the kind of relationships they create between people, the kind of emotional space they occupy, and the forms of possible life they point toward. As we said, raves are collective experiences, but the way they are collective is unusual. They could be mistaken for an individualistic experience: an individualist cult, everybody dancing alone, in the edges or the center of a big space, staring only at the speakers. Only if someone attends a party themselves can they understand that the collectivity of a rave is defined in a meta-level. It isn’t the group of people, the conversations, the collective dance, the social norms and the stress all those entail. Raves, like Fisher says, are both a symptom and a transcendence of their age, and that’s the reason they can be stress-reducing experiences. The colors, the drugs, the thud of the bass, all of them often seeming only replicas of things, offer a fertile ground for depersonalization. The collective acceptance of behaviors that in other contexts would certainly be socially awkward offers a very direct release to desire, as the subject that has and acts on those desires both is and isn’t you. What are the consequences of this collective-beyond-the-coll ective in the lives of ravers outside the raves, and which is its fullest political interpretation? Those are matters for another time.

AND NOW EACH STEP TOWARDS TRANSCENDENCE CREATES A NEW NORMALITY

AND THE GLUTTONY OF PLEASURES WITHIN PLEASURE ARE LIKE DEATH

AND NEW ANXIETIES LURK IN THE DISTANCE

Flow Coma → George Moraitis → digital print (2/3)

Flow Coma → George Moraitis → digital print (2/3)

List of Damages & Offerings → Giannis Galiatsos

Its Name is Red → Giannis Galiatsos

Flow Coma → George Moraitis → digital print (3/3)